When Monica Brashears’s debut novel, House of Cotton, released in April 2023, it was described as a “bizarre, uncomfortable read in the best way possible” (NPR) and “meditates on moral dilemmas in fresh, haunting ways” (NYT). The novel follows Magnolia Brown, a young Black woman in Knoxville, Tennessee, who – while grieving her grandmother’s recent passing, working a low token job at a gas station, and fending off a predatory landlord in more ways than one – accepts a lucrative position with an enigmatic and visionary funeral home owner named Cotton. The job entails modeling and “inhabiting” the looks and personas of deceased loved ones so families, friends or ex-partners can achieve some closure around these losses and say goodbye over video chat. Meanwhile, complications begin to mount for Magnolia as her dead grandmother makes frequent appearances to her, threads connecting Magnolia to her old world start to unravel, and the requests from mourners and Cotton become increasingly demanding. Magnolia must decide what to sacrifice in order to free herself. The novel is a fresh, enchanting take on the way society views Black women and the expectations and assumptions they must bear.

Now, one year after its debut, House of Cotton is being released in paperback. In our interview, Brashears discusses her journey since publication, how she works at the sentence level to achieve her signature prose style, writing a novel rooted in the place where you’re from, and where Southern literature could evolve.

The first thing that struck me about House of Cotton is Magnolia’s voice. It is one of the strongest voices I’ve read in recent memory, sophisticated and sharp at the same time. Did the voice first emerge when writing the original short story (which became the novel) or did it emerge while getting the plot down?

I drafted the original short story as a baby writer in undergrad. I shelved it with no plans on returning because it felt stiff and somewhat inauthentic. It wasn’t until later that Magnolia’s voice came to be, which I think is what allowed me to sit in the world as it evolved to novel.

Your novel works incredibly hard at the sentence level, blending musicality and detail and lyricism in a way that brings to mind Lauren Groff and Jesmyn Ward. It’s stunning. I loved every bit of it. This lyrical tone envelops the reader in visceral language and transmutes what could be a bizarre plot into a surreal and sublime experience. How do you approach the art & craft of the sentence? What inspires you?

Thank you, that is very kind. I think a big part is fostering an awareness to the language that tickles my gut. (Love the words tickle and gut). I have a running list in my notes app of words I keep returning to. The other half of my approach to the craft is studying writers whose sentences I admire. Sometimes I perform autopsies on them to figure out how they’re doing what they’re doing. Sometimes I just let myself sit with the pause that comes after encountering them.

The novel is set in Knoxville, the town you’re from. How did you feel about writing fiction set in a place you’re so deeply familiar with, but that’s small enough that others might recognize or try to hold you to specifics? In other words, how do you capture the universal “truths” of a place others know so well while bending it for storytelling?

I was living in Syracuse when I began drafting, and I’d never experienced true winter until then. I found myself missing Southern summers, the way they cling to you. I also wanted to add imagined history that felt like branches from the systems which have shaped Knoxville; I wanted to manipulate the geography a bit. There were moments I struggled against the logical voice in my head (the foe to fun narrative). I think throughout the drafts, there was a slow settling into self-granted permission. And so I began to literally move mountains in the plot. I think if there is an earnest psychological/sociological exploration happening in a narrative, then that bending of place becomes easier.

The majority of Magnolia’s moments in the novel exist in the space between sex and death — the blooming and decay, the building up, the breaking down, change being the only constant, so there’s no real period of “rest” for Magnolia and Mama Brown in this story, only the people who have the privilege to rest. Could we talk a bit about this larger theme of Black women being exploited and why you wanted to tell this theme through this particular story?

I’m obsessed with the poetry in this question. The in-betweenness felt right for a novel so concerned with the effects of the exploitation and the personal and generational trauma. On a craft level, I think we’re all drawn to contrast — the bloom is pretty on its own, and the decay is something to consider, but when paired together, I think the energy begins to form. Those juxtapositions work well when depicting a character like Magnolia, who has experienced more than a person should. (Preface: please excuse my rudimentary understanding of neuroscience) The way a brain interprets its environment after being subjected to trauma, too, captures the destruction and the reconstruction. The communication between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala are altered so that the brain interprets the past events as occurring in the present. If intervention hasn’t occurred, how can one rest? Similarly with the effects of generational trauma and looking at the root cause — the impacts of slavery still shape America. These impacts are vast and evolving and cyclical. Those who have benefitted from this are those who rest.

Magnolia’s connections to the natural world and remembering Mama Brown’s plant wisdom help her step into the only power she can harness (using plants for tea, having sex in bushes and backyards, grounding herself with honeysuckle). Appalachian plant wisdom is a subtle and welcome thread throughout the book. Can we talk a little bit more about this?

Yes! I grew up fascinated by stories of a long-gone family member who was a granny witch. There were more subtle ways it shaped my childhood, like knowing tobacco is good for stings and hearing whispers of who might hunt ginseng. I also wanted to weave in Hoodoo as it’s been demonized (which is ironic considering how terrifying white Southern Baptist churches can be). In part, I was reaching into that area that felt like magic to me as a child because of course I still find it interesting. Plant knowledge offers hope and the feeling that anything is possible in your own backyard; you just have to know what you’re seeking. Magnolia, I think, needed that hope and healing.

Before the novel, before the short story, what was the inkling of inspiration that started House of Cotton?

I wish I knew the answer to this! I think growing up poor in a mostly poor county and navigating college felt so strange. People had nice shoes and spoke of allowances. My very best guess is that the inspiration came from feeling alien and trying to make sense of Institutions with a capital I.

It’s been about a year since the debut of House of Cotton. What has the journey been like for you post-publication? Do you have any advice for writers in this first year following their book being out in the world?

It’s been such a beautiful tornado. This advice only applies if the writer is as neurotic as I am: Let yourself sit with all the good that comes during that first year. It’s easy to fall into the more-more-more mindset with reviews or awards or lists. You wrote a book! Your book has likely moved someone or allowed them to see the world differently, even if just for a bit. Treasure that more than anything.

How do you see contemporary Southern literature (particularly gothic) progressing, and is this a place you’d like to stay in as a writer or do you want to explore other genres?

I think I’d like to see more genre-bendy Southern gothic literature. I’ll always be writing from my roots, I think. It’s hard to know where my little obsessive heart will take me.

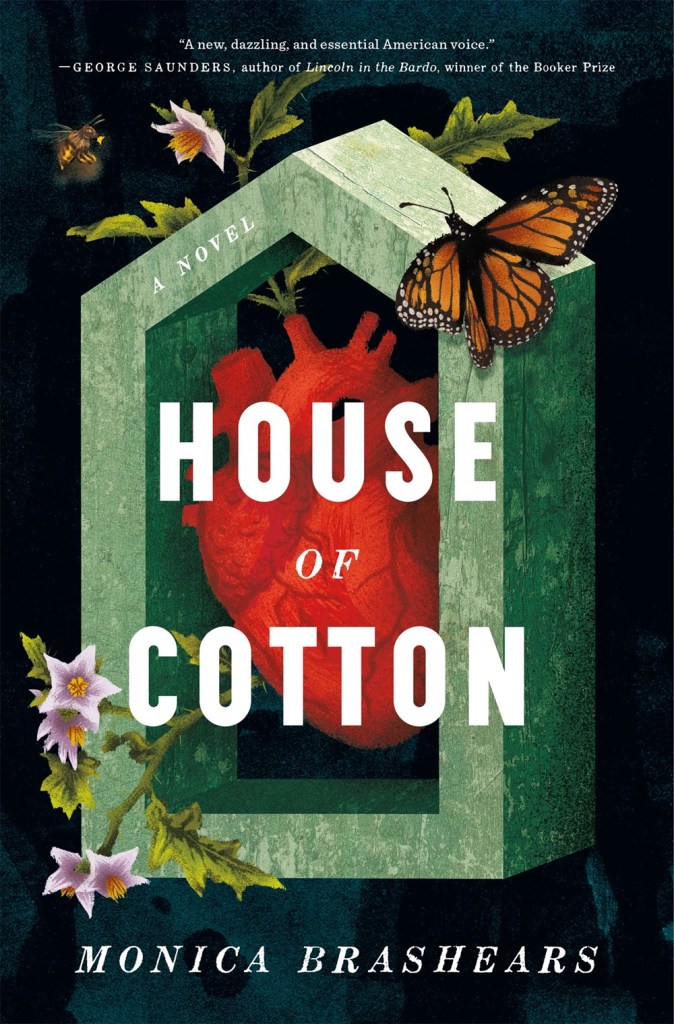

FICTION

House of Cotton

By Monica Brashears

Flatiron Books

Published April 4, 2023

Papberback April 2, 2024